hearing Searows and reflecting on the rain

In my six or so years residing in Southern California—a place habitually blanched in sunlight—there have been a few chapters when it seemed the weather obliged my mood, my psychological state, and the very particular thing I was navigating at the time. Two of these chapters involved not the typical, reigning sun but the provisional, visiting rain. Day after day of uncommon rain. Gray, muted-blue skies and rain. A weather event to say, “Time to change it up.”

The first such chapter, a few years ago, I dug deep into the archives of an old email account and reread thousands of emails exchanged between myself and a former lover who lived at a distance for most of our relationship. He lived—and for a time I lived with him—in a notedly damp European city nestled near the sea. A decade removed from that love affair, I sat at my computer in my apartment in California, and the rain beat steadily on the roof and outside my windows, offering a cocoon for me to process that earlier, rainier era of my life. The weather and the words transported me to a former place and time. Days passed. Days of reading, integrating, and deleting most of those emails. It’s as if the rain was there to say, “Go on, rinse the sediment from your bones. Keep what’s dear and release the rest.” And when the project was complete, the rain cleared.

“It’s gonna rain soon

And pull me back in

Whatever it takes

To fill the shape I’m in”

The second chapter—beginning two weeks ago—, not only did the weather oblige but also the soundtrack. Spotify recommended Searows’ latest release, the song “Dearly Missed,” from his upcoming album Death in the Whaling Business. Was it that the algorithm knew a combination of things at once: that Searows’ PNW-influenced sound would hit just right as a storm reached the coast; that I needed to batten down the hatches of my own psyche to weather the eye of yet another intense life transition; that I needed sound and scene to support me in that, a sort of universal mise en place?

Whether algorithmic phenomena or a blessed coincidence, things align sometimes. Things align beautifully.

I melted quickly into the sound of “Dearly Missed” and thought, This is perfect. Searows is perfect for this weekend. I need to go deeper into the discography. Enter his debut album from 2022, Guard Dog, an album I had never taken time to hear before. In one sentence, this album is described as a rain-soaked, intimate confession; quiet folk woven with raw longing, memory, and the ache of someone trying to tell the truth gently.

Thus, Guard Dog became the soundtrack to my rainy little SoCal life this past couple weeks.

Guard Dog album cover

Searows

And what can I say? Much about the rain, much about my life, much about how beautiful is this music. If the phrase is “You had to be there,” then now it’s “You’d have to hear it.”

“It’s part of me

Wouldn’t you believe it’s nothing?

It’s all you need

When you keep the rain from coming”

A rainy week to myself with admittedly melancholy music was the balm I needed. I was physically ill, as well, with laryngitis rendering me speechless: another prompt from the universe to go silent, reflect, listen deeply. I listened not for words but for feeling. I attuned to the gorgeous frequencies of Searows’ voice, but I didn’t strain for the lyrics those first several listens. The sound seeped in, its own wordless meaning.

City life has a way of occluding the vital undercurrents of my being, particularly in times of transition and mere survival. The freeway roars, merges, passes over and under, intersects, speeds toward a million arrivals, and it all makes sense, but it overwhelms. Windows stack atop and beside each other, portals to the private lives of a hundred residents in a single square block. Crows perch on the power lines. Builders drill and build. Children fuss and parents stop for coffee. The stores blink their lights. I struggle to grab ahold of myself.

I’ve always been someone with a wide aperture. Developing the instinct for narrowing the focus has taken time, experience, maturation. The city is beautifully stimulating but I’m learning to honor my mind’s unique filter. In such a sunny city, too, where the light reveals generously, a rainy, overcast week is a gift to the burdened psyche. The rain lets the mind, heart, and soul be their own light and guide. It says, “Everything is dimmed. Go inside. Feel around. Without much sensory stimuli, come back to your senses.”

With or without the aid of weather, music is a trusty companion and co-regulator in times of need. I’m thankful for Searows’ stunning music helping me to sink into myself and soothe my system this past couple weeks.

As I write this, the sun has returned and the city is abuzz with the holiday season. Change is the only constant, they say, but maybe there is a spirit that stays constant beneath the change. Rainy skies and real music remind us of this spirit.

“But when it’s said and done

I’ll be the north star that takes you home”

feel, feel, feel! they bade

you must reach the waterfall

the birds called my name

How to Make an American Quilt

My mom loved the movie How to Make an American Quilt (1995), so I saw it a few times growing up. A great cast including Winona Ryder and Maya Angelou, if you had asked me yesterday about the plot of this film, I would’ve slowly pieced together… “Winona’s character goes to her grandma’s house for the summer to work on her writing. Her grandmother and grandmother’s friends work collectively on a quilt and tell stories. Winona meets up with a lover in the orchard…”

And that’d be the extent of my memory of the plot. We remember the essence of things, don’t we? Speaking personally, I have always taken in information somewhat impressionistically, Gestalt-like. I remember feelings; I remember the whole; I forget the details that make up the whole. Maya Angelou herself said, “People will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.” I suppose this concept applies to memories of not just persons, but also films.

An important detail I had forgotten is that the main character, Finn (Ryder), is a 26-year-old woman engaged to be married. “How do you merge into this thing called a couple…,” she narrates at the beginning of the film, “…and still keep a little room for yourself?” Sam (Dermot Mulroney), her sweet and earnest husband-to-be, begrudgingly drops off Finn at her great-aunt’s place in the country for the summer. She needs to focus on writing her master’s thesis, she says.

While writing and applying herself to her formal education, Finn receives an informal one, as well. The theme of the quilt being made by her relatives is Where Love Resides. Finn’s grandmother tells her, “It’s your wedding quilt, honey.” Finn takes in the stories of her elders and wrestles with her feelings about marriage. Uncertain about the fate of her own union, she digests tales of all that can go wrong in marriage: betrayal, infidelity, death, abandonment, unplanned pregnancy, the loss of self to a role (motherhood), and so on.

I re-watched How to Make An American Quilt yesterday evening because I spent the weekend quilting. The film seemed a natural choice. Saturday I attended an Intro to Quilting workshop. As I completed my first-ever half-square triangle, the instructor exclaimed with delight, “You made your first half-square triangle! Congrats! Want to take a picture?” I grinned widely, happy and satisfied with what I had produced, but when asked about the picture I quickly said, “No!” Mere seconds later, I retracted. “Well, maybe I do!”

Making 4-square patches and half-square triangles

Can’t remember the last time I cheesed this hard for a photo.

I caught the bug. “Quilting is a great hobby for people with OCD,” the instructor joked with another student across the room. The exactitude, the math, the triple checking, the care, the detail requires a meditative level of focus. In contrast to garment construction, another craft I am learning, quilting has a cozy rote-ness to it. In repetitive fashion, I can spend an hour creating ten half-square triangle patches without much higher-order thought. Precision and focus, yes, but not too much analysis.

A quick Google search tells me that quilting dates back thousands of years and that European settlers brought quilting to the U.S. in the 17th and 18th centuries, utilizing scraps of fabric to create bedding. My maternal grandmother (1934-1994), a third-generation American, likely developed the skill in the 1940s and ‘50s, both as ancestral homage and a cultural convention of the time. I can’t say exactly when she made the quilt shown below, but it’s at least 40 years old, and it’s been a seasonal staple in my bedding.

Heirloom quilt by my maternal grandmother (1934-1994)

ChatGPT suggests that my grandmother’s quilt is a traditional patchwork design based on a Double Irish Chain variation. The plaid inserts indicate scrap or recycled shirting fabric, a common practice in historical quilting traditions, and it appears “hand-pieced and hand-quilted, judging by the visible stitch irregularities and gentle texture (puckering) from hand quilting—signs of authentic craftsmanship rather than machine production.”

I’m not sure about the hand-pieced and hand-quilted part. I would guess she used a home sewing machine. How I would have loved to ask her about it.

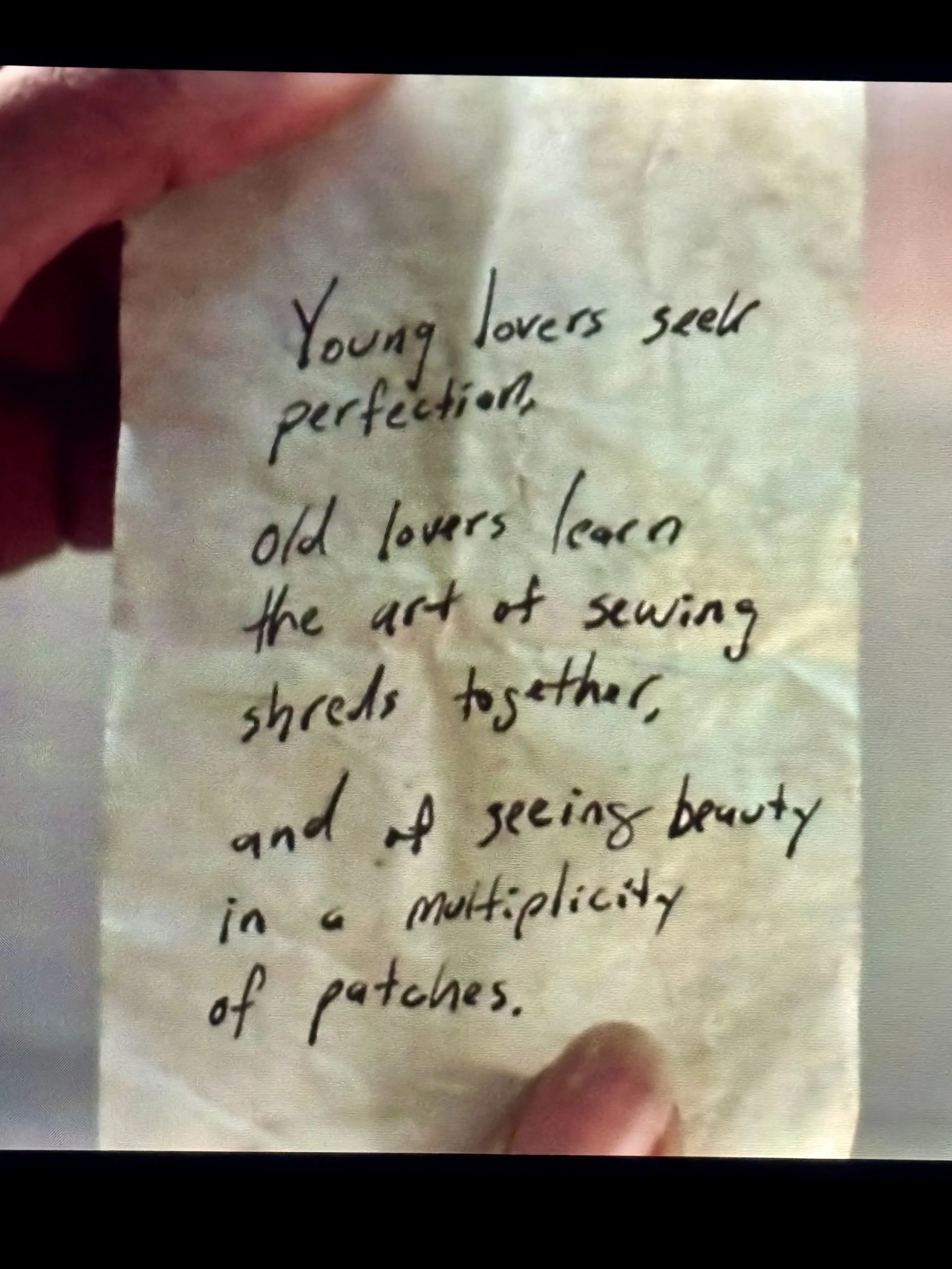

The art and craft of quilting lends itself to many beautiful metaphors, but for now I want to borrow one from the film. A member of the quilting bee shares a poem with Finn.

Old Lovers

Young lovers seek

perfection,

old lovers learn

the art of sewing

shreds together,

and of seeing beauty

in a multiplicity

of patches.

No expert on love, I understand that relationships come apart at the seams sometimes, or perhaps they were never sewn with a sturdy seam in the first place. Regions of the heart become scrappy; romances catch snags and tear apart; wholes become fractions. Histories dissolve into memories, and memories dissolve into impressions long after events have passed. We remember how things made us feel, but the parts are fragmented and forgotten.

The old lovers in the poem, however, are like quilters. They find value, meaning, and transcendent beauty in the shreds, the scraps, the patches. They see love as something worth sewing together, despite its flaws, its mistakes, its shortcomings. I am touched by this metaphor and think maybe, if I can learn the art and craft and tenacity of quilting, then I can understand better how to construct love of a similar quality.

giving away my paintings for free

If I can’t sell my paintings, then I may as well just foist them upon people.

This morning, I struggled my way out of bed around 8am, loosened up my hamstrings with some yoga, then ran errands on foot around my neighborhood. The first stop was a house a block away from my apartment. A couple years ago, while doing my neighborhood walk, I stopped beside this house and snapped a picture from the sidewalk; a beautiful red and purple flower shot out of the landscaping. I turned that photo into a painting:

Indian Shot

acrylic on canvas panel

June 2023

San Diego

The painting had floated around my apartment in the ensuing years, until I decided this morning to gift it to the homeowner. An identical story accompanies the following:

Cypresses

acrylic on canvas panel

April 2025

San Diego

At each house this morning, I tried to surreptitiously drop off the painting near the front door. In neither case did my scurrying avoid notice. At the Indian Shot house, I leaned gently over the front fence to drop the painting on the lawn just as the front-porch door began to creak open. I did not look up long enough to see who was opening the door. I dodged the opportunity to provide an explanation for my behavior by quickly carrying on my merry way.

At the Cypresses house, it was not a human but a security system that took notice, alerting me of its detection with a long, low beeeeep. Again I scurried away.

Mission accomplished. The idea is that these homeowners would likely appreciate paintings of their properties more than any art-collecting stranger on the internet, not to mention I am yet clueless as to my ideal customer, so we’re going guerrilla on the marketing for now. Boots on the ground. Erm, rubber-and-foam tennies on the ground.

As I paint more, I create more paintings. These paintings need somewhere to exist. If they exist in my apartment, they take up space and make me feel cluttered. I do not like that feeling. I dream of a day when I have an actual studio space, where I can be messy and cluttered as hell and then can close the door to that space and go on living in my tidy and relatively minimalist environs.

Luckily, bad paintings can be thrown away or burned, and I utilize that strategy frequently these days what with my foray into oil painting. I am just so, so new at it and so, so unskilled and so, so impatient. I love the visceral sensation of painting—the movement and the connection of brush to canvas—so much that the creative act feels aggressive, almost angry, like I am mad at it for not making sense yet.

The fury also comes from a drive to annihilate the inner critic, to move before I am inspired, to reclaim all that time I held back my creative urges—through jobs, schooling, adulting, doubting, all the things that slow the damn roll if we let them. My shitty painting feels like vomiting, purging all that. It’s rebellious. It’s a “fuck you” to everything that has ever held me back, primarily myself. It’s an ego death. It says, “I can use my hands and my body and my mind and my soul and make things and fuck up and not produce anything valuable and still be here, still have the right to exist, still have the right to express.”

Speaking of the responsibilities of daily life, my creative time is up for the day. I’ll end this post by stating how thankful I am that I can upload digital photos of my work (like those above); the images can own their tiny little lot in the universe; and then I can discard the physical, material art itself. Thank God for the cloud.

Admiring Wes Anderson's The Darjeeling Limited (2007)

I kept telling a friend he had to see The Darjeeling Limited, because he works as a train conductor and I knew he’d get a kick out of Wes Anderson’s deliciously quirky style. He recently watched it, so that was my cue to plop down on my couch and savor this film once again for myself, delighting in seeing it through my friend’s eyes, or trying to.

An aside: I haven’t yet developed a “Top 10 Favorite Movies” list, but this may be on it. In competition with The Royal Tenenbaums, I think The Darjeeling Limited is my favorite Wes Anderson film.

Like a great book, each time returning to it is a new experience. There were plenty of scenes I had forgotten. It was awesome to see Owen Wilson, Adrien Brody, and Jason Schwartzman—beautiful actors—play brothers and follow such a tight, emotionally penetrating, often hilarious script. “Did I raise us?” Owen’s character Francis asks his two younger brothers from across the train table, leaving inadequate time for them to respond before jumping up from his seat to ask the steward for a power adaptor. Like so many great moments in art, the profound is juxtaposed with—yet inextricable from—the mundane.

Francis is the organized, responsible leader who’s been conditioned to conceal his inner chaos, common for an eldest child. Peter (Brody) is the melancholic middle child, often unsure of his place and purpose yet stronger and more capable than he imagines himself to be, and Jack (Schwartzman) is the baby, a constant witness to the shenanigans of his older siblings who nevertheless asserts his individuality—often furtively and rebelliously. “I’ll be right back,” he says suddenly, leaving scenes when the emotional charge between his older brothers runs high and he needs reprieve.

The birth-order trope of course evokes the invisible characters who loom large in the background: the parents. Dad has died and Mom is still existentially present but physically and emotionally departed. Qualms flare between siblings as to who is whose favorite and who will inherit what. By the end of the film, however, the strengthened bonds between the brothers suggest an equality and solidarity in brotherhood that transcends the limitations and failures of the parents.

We think about our lives when we watch the characters’ lives play out on screen. I certainly thought of my own siblings and parents. At other moments, we as viewers are jerked out of our own reflections by the sheer beauty and artistry of the scenes. One such scene that struck me last night was when the brothers get kicked off the train and are left in the desert at night. Around a bonfire, they pass around their leftover bottles of airline liquor and “get high” on Indian sedatives. They each grasp a sturdy, burning torch as they exchange heartfelt words. The vast, dark, desert sky presses in around them. Debussy’s “Claire de Lune” emanates as the soundtrack.

Wes Anderson may be a master of what I’ll call tasteful kitsch (an oxymoron, I know). A scene like this, while so unrepresentative of reality and so glaring in its artistry, shears off all of reality’s trappings and cuts straight to the heart of things. The truth is often beautiful but too cluttered by reality to see. Scenes like this bring us back to the source.

As long as I’m veering into sentimental territory myself, I’ll end this post with a final reflection on the scene that always flashes in my mind when I think of this film. In fact, it’s never when I’m actively thinking of this movie that I think of the scene; it’s when I’m pondering my life as a whole that this scene comes to mind.

Almost the final scene, the brothers have to catch a train out of the place where they have just visited their mother. They’ve just made it to the platform with all their luggage, but the train takes off without them. They begin to run after the train, strapped with all their baggage. They realize they need to let go of the luggage, to release all that weight in order to run fast enough to catch the train. So they do… and they catch it, victoriously. (Sorry for spoils!)

If this scene isn’t a metaphor for my life—and many of our lives, I’m sure—then I don’t know what is. So many times I’ve felt like the kid who clings fiercely to the “known,” to my own narratives, who tries to control my fate with each stride, only to find out that the train hasn’t waited for me and I have to run like hell—to sprint with desperation and abandon—to catch it. Life is a leaving train. To catch it, we must drop our weights: what we thought we knew, who we thought we were, where we thought we were headed. We have to put aside our pride and chase after it.

I’ve been that person so many times, the one who chances missing the train but makes it in the end, fresh out of breath, disconcerted but relieved as hell… Maybe even victorious. I love this movie for many reasons but especially for capturing this feeling.

tender Graces

here now

tender Graces

and Muses with beautiful hair

~ Sappho

Underthink It

Heaven must be a sunny apartment in Southern California, a homemade cold-press latte to sip at 10am, paint supplies, and a whole day to follow one’s muse.

My mantra for stepping back into the creative flow is UNDERTHINK IT. Everything is a mess. Nothing is routine. I have little idea what I am doing. I embrace the archetype of the fool.

Something about discovering and watching the painter Ellie Harold the other night before sleep lit a fire under my proverbial ass, and I woke up with a creative verve that has not visited me in months.

So yesterday, exactly a month since I walked out of my final class as a masters student, I started painting again.

I spent that month recovering. My body crashed almost exactly as the masters program ended, buckling under the pressure of everything going on. It was a pretty bad respiratory infection that kept me horizontal and sorry for myself for longer than I wish to detail.

I’ve been watching reruns of One Tree Hill and stressing about money and eating junk and despairing over my perceived soul depletion and fearing the unknown. When will I earn my next paycheck? Where will I work? Will it take until retirement to pay back my student loans?

As an act of rebellion, I am saying “fuck it” and just standing in front of that easel, listening to good tunes, and trying to feel the sacred movement of the clock as something more than a measure of economics.